Irish Woodturners Guild Journal – December 2003 – Issue 28

Francis Morrin went to see a new commercial timber operation which traces each plank right from the source to the end use.

[two_fourth]

The Lisnavagh Estate lies in rural Co. Carlow, just a short distance outside the picturesque village of Rathvilly. Like many estates it was left with a legacy of fine woodlands along with farmland, buildings etc., that many will be familiar with.

However, just as all rural life and especially farming has been hit by the changes in modern farming practices brought on by EU policies, Lisnavagh has had to change and diversify to survive.

[/two_fourth]

[two_fourth_last]

[/two_fourth_last]

[clear]

Part of this diversification has been to examine the resources left on the estate and in particular at the woodlands. The result of this examination was a new development for those who use and are interested in wood, the Lisnavagh Timber Project.

“We realized that wood is important as a material to its end users and started to look at ways we could service that need” says William Bunbury, director of the project. “We decided that we would start to collect timber as it fell around the estate, but not only that, we decided to catalogue every piece that we collect so that the timber is completely traceable” he says. The project was some time in development while William constructed an advanced computerised database which would service the needs of the project and yet be easily accessible. This database can track where the timber came from (along with photos of the tree before harvesting), timber quality, size, distinguishing features and more. This database is at the heart of the project.

[two_fourth]

[/two_fourth]

[two_fourth_last]

The process of harvesting timber begins by collating reports of felled trees and/or trees which need to be removed for various reasons.

Each tree is visited and photographed, then details of the tree such as size and distinguishing features are noted, and it is then labelled with a unique serial number.

This number then stays with that timber for the rest of its life.

[/two_fourth_last]

[clear]

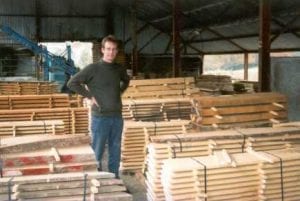

Back in the office, the information is added to the database. When enough trees await conversion, they are collected and brought to the milling area where a mobile bandsaw mill is used to convert them. The timber is cut primarily for furniture i.e. 1 inch planks but some is always cut for heavier planks too. “We also keep a stock of the burrs and highly figured timber we come across for turners and sculptors – usually 4 inches thick” adds William. Each plank is numbered from the original tree as it comes off the mill and sticked out for air drying.

William follows established rules for drying “We stick out the timber in a covered but open walled shed to allow it to air dry using the 1 inch to 1 year rule before moving the timber on to the kiln” he says. During this time of sticking out, the timber is constantly checked and the ties that are used to bind the piles together are tightened as the timber shrinks during drying.

[two_fourth]

“At the moment we kiln the timber in batches” explains William, “and after this final drying we keep the timber in a dehumidified room to prevent the moisture content of the timber re-equilibrating with moisture in the atmosphere”.

“All of the timber is listed on the database – along with the stage it is at” says William, “so that we can service exactly a woodworkers needs. Furniture makers may need timber at a lower moisture content than turners for example and we can supply that”.

[/two_fourth]

[two_fourth_last]

[/two_fourth_last]

[clear]

Such details obviously affect price with kiln dried timber ranging in price from €20 to €50 per cubic foot (plus VAT). On request, customers can have a report of the timber currently on hand and in what dimensions so that they can choose according to their needs and if they purchase, each lot is accompanied by a certificate stating the source of the timber and a bit about the timber for the end source.

I ask William what he has planned for the future. “Well, we definitely need to expand sales to higher levels and also we need to invest in some more machinery” responds William. The Lisnavagh Timber Project seems to me to be unique, – at least I haven’t heard of anything similar anywhere – and probably sets a benchmark for many timber suppliers both at home and abroad.